Mark Wallinger

State Britain, 2007

installation, mixed media

43 meters

As originally conceived and commissioned for the Duveens Commission at Tate Britain, 2007

Copyright of the artist, Courtesy Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London

Photography by Dave Morgan

Simulacrums of Protest

October 2009

Reem Fekri examines Mark Wallinger’s installation ‘State Britain’, also placing it into the theoretical context of Jean Baudrillard’s The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.

Plato wrote on two different types of replicas of the real. He defined the replica as being a precise reproduction mirroring the original, while the second is intentionally distorted yet appears original to the viewer. In recent times, postmodern theorist Jean Baudrillard argues that a simulacrum is not simply a copy of the real, but becomes a truth in its own right, such as ‘the hyper-real’. Having recently read Baudrillard’s The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, it brought back memories of Mark Wallinger’s installation State Britain, which was nominated for the 2007 Turner Prize.

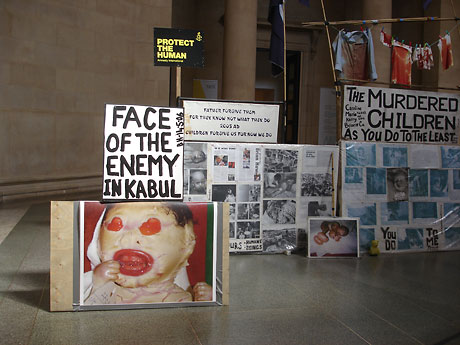

When Wallinger was nominated for this provocative installation, it conjured up an enormous amount of criticism from the public. At the time of the prize’s exhibition at the Tate Britain, the installation appeared awkward and uncomfortable within the temple-like interiors of Britain’s national gallery. The remnants of an anti-war protest were laid in the Duveen Galleries, stretching to a remarkable 40 meters wide. Replicas of anti-war paraphernalia occupy this space, including banners, signs, toys, and images of victims of war placed in a neat line along this hall. Whilst the title of the work suggests the current political situation in Britain, it also indicates the literal territory as well as the current condition of the state itself.

It comes to no surprise when one learns that this installation is a replica of Brian Haw’s protest, the peace activist that camped outside the houses of parliament. Wallinger successfully recreated this illegal protest within the confines a public art gallery. Alongside this, Wallinger marked out with black tape the one-kilometer ‘Exclusion Zone’ radius in which one is allowed to protest from parliament, and juxtaposing this to its literal context, this zone cuts across the Tate Britain, placing the work half inside and half outside the border.

Clarrie Wallis, the curator of the exhibition, argues that Wallinger delineates a clear distinction between protest and art; by utilizing his artistic abilities, Wallinger is able to debate ideas surrounding freedom of expression in Britain within the confines of a gallery. Perhaps this is successful simply due to the fact of the dissimilarity between the gallery itself and installation. The two lay in complete opposite aesthetics, and within this particular piece, there is an underlying political awkwardness that is challenging to look at.

On May 23rd 2006, Haw’s personal possessions and placards were removed from the opposite side of the Palace of Westminster, a space which he previously occupied for five years, and instead was allotted an area on the pavement that measures just three meters by two. Presumably through this installation, Wallinger gives Haw an extended voice, which had been taken away from him.

This all mirrors Jean Baudrillard’s theory of simulation, which he delineates into three levels. At its primary level, a palpable copy of reality is used; at the second level the copy is acceptable for it obscures boundaries between reality and representation, which in turn confuses its viewers. The third and final level of simulation generates a reality of its own without being based upon any particular fragment of the real world such as virtual reality, previously mentioned as the hyper-real.

Conceivably, the second level of simulation is representative of Wallinger’s recreation of Haw’s protest as an original demonstration created to reveal appalling reasons of war and conflict to large political figureheads through signage, individually created posters, found objects and printed images to an exact copy that Wallinger created. Through this ‘replication’ protest, which had been produced in a studio with two assistants, Wallinger managed to recreate a simulacrum of protest. There exists an element of hyper-reality within this installation. Wallinger lacks in identifying with any kind of struggle or anguish that peace protesters have to go through in order to have their voices heard. As an already established artist with gallery representation, he has yet to go through any distress that Haw experienced. However, on an exasperating note, he successfully manages to create a protest that replaces its original version. It achieves a level of believability to the extent that Haw’s struggle becomes repressed in the minds of the viewer.

Drawing on Disneyland as an example of second and third level simulation, Baudrillard argues that ‘…Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real…’ Fake castles, for example, appear more real than actual castles for this is how we have imagined them to be. Similarly, Wallinger’s piece seems more real than the original for reality and representation become blurred together.

Susan Sontag gives further examples of reality based on illusion. Through her writings on the photographs taken of Iraqi soldiers being tortured in the notorious Abu Ghraib prison, she maintains that the photographs were an illusion of reality, arguing that it is impossible to consider the pain and brutality that occurred during these times of conflict, despite looking at these images. Equally, it is impossible for us to consider the struggle that Haw went through to have his voice heard. What we view at the Tate Britain as a simulacrum of protest is not a realistic representation of Haw’s experiences.

The piece raises an extensive series of questions, but there is no final assumption to the work. Perhaps this is part of the brilliance of Wallinger’s installation, the fact that there is no absolute conclusion that can be conceived, and therefore one cannot help but address the ideas of political freedom he is trying to make. Additionally, the controversy surrounding ‘State Britain’ raises questions regarding issues of originality and authenticity. Haw was given work by Banksy and Abby Jackson, which had then been duplicated by Wallinger or his assistants for the installation. If we consider that these are ‘copies’ within another ‘copy’, we enter a larger realm of hyper-reality.

As in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, Baudrillard argues that images broadcasted on televisions via Western media were so heavily edited that they did not depict what actually happened, posing the argument which rightly challenges the majority of people who believed what they saw on their television screens. This mirrors Wallinger’s treatment of Haw’s original protest. Few people know what struggle Haw went through, yet Wallinger appropriated Haw’s creation and successfully contrived it for a prestigious art award. Questions remain unanswered regarding authenticity; yet, Wallinger gave Haw an extended voice - a voice reaped away and withdrawn from him. Wallinger chose to create a politically charged installation meant to be perceived as aesthetically astonishing due to its beautiful awkwardness in the Duveen Halls.

Although Wallinger’s piece does not relate directly to Iraq or the Arab world, he deals with issues of utmost relevance to the ‘Arab world’ (examined as a generalized whole) as an artist from the West, and Baudrillard’s theory of simulation resonates profusely in discourse related to the socio-politcal contexts in which Arab art production primarily occurs. Similar to Jermemy Deller’s recent piece It Is What It Is: Conversations about Iraq (2009), where Deller, over a six-week period invited journalists, Iraqi refugees, soldiers and scholars to discuss memories of the last decade in Iraq. The exhibition’s main focus directed itself towards a car that was destroyed in an attack in a crowded book market in Central Baghdad. Like Wallinger, Deller addresses sensitive political issues regarding the illegal ‘war’ or military occupation of Iraq by bestowing such political gestures in art galleries and creating a platform for discussion with regards to these issues. Although their identity lies solely on Western grounds, they both deal with issues relating to the Arab world and Iraq with sensitivity, presenting both the trauma and struggle that the region is enduring.