The Mosque of al-Hakim, 1995

Wood, glass, card, rohacell, paint, lacquer

90 x 125 x 14 cm

Photography by Steve White

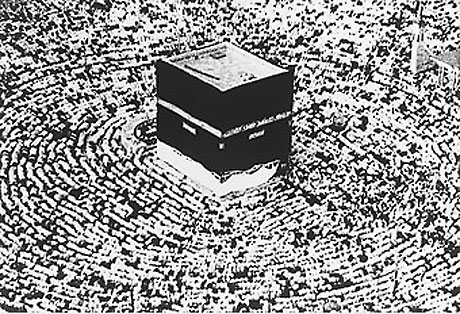

Mecca, 2002

Woven cotton

122 x 183 cm

The House of Arabs, 1990

Wood products, glass, paint, cellulose lacquer

180 x 220 x 15 cm

Conceptual Architectural Representations of the Arab World: the Artwork of Langlands & Bell

October 2009

Muraqqa editor Alexander Barakat reviews the architectural ground plans depicted by British conceptual artists Langlands & Bell relating to the Arab world based on an interview correspondence Barakat conducted with the artists.

Having exhibited their originative and deviceful digital model of ‘The House of Osama Bin Laden’ six years ago, earning both a Turner Prize nomination and a BAFTA award for Interactive Arts Installation, conceptual artists Langlands & Bell proved that they can embrace complex Middle Eastern subjects of a highly controversial political nature in both a diplomatic and erudite fashion, exemplifying their intrigue without exoticising them to both a Western and non-Western audience, also permitting a convergence of various perspectives and stimulating discourse to promote a more constructive understanding of their given subjects. ‘The House of Osama Bin Laden’, however is certainly not Langlands & Bell’s first attempt at exploring themes relating to the Middle East, as their artistic practice also encompasses several works pertaining to the Arab world produced over the last two decades, including: ‘The House of Arabs’ 1990, ‘The Great Mosque of Ibn Tulun Al Qatai’ 1991, ‘Mecca’ 2002, ‘The Mosque of al-Hakim’ 1995 and ‘Enclosure and Identity’ 1996, with the first three mentioned examined within this article.

As artists of British origin examining such structures from an alien yet educated perspective, several bases motivated them to produce work consisting of representations of buildings from the Arab world. A primary motivational factor was simply their appreciation of the particular formal and aesthetic beauty of which these structures embody and their potential to signify the beliefs of these structure’s respective populations, a vital role fulfilled by architecture that can be examined in a vast range of social contexts. The duo acknowledges the Arab world’s utmost importance in today’s socio-political arena and perceives it as natural for them to desire to visit it in their work.

Examining Langland’s & Bell’s earliest Arab architectural representation, ‘The Mosque of al-Hakim, Cairo’, 1995, (wood, glass, card, rohacell, paint, lacquer – 90 x 125 x 14 cm), the white reconstructed mosque commissioned during the reign of the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim is intentionally placed against a black background in order to isolate the building by levitating it into a dimension detached from a precise reference point, for it exists within both the realms of time and space. The formal composition of the sculpture functions as an aid for contemplation, permitting the viewer to perceive the building in the present, which also directs one’s attention towards the architectonic attributes of the building. In addition, one should refrain from over analyzing certain visible architectural elements in the piece, such as deployed motifs reminiscent of a fortified military structure premeditated in the original plan of this sacred space, and the associations and connotations they provoke, for the artists do not intend to devise or formulate either academic or didactic points in their work. Nevertheless, Langlands & Bell do observe that past histories, or a certain awareness of the past, dwells in the present when one envisages the existence of a building like the mosque of al-Hakim.

Diverting away from Cairo to ‘Mecca’, 2002 (woven cotton, 122 x 183 cm), their most recent piece produced in the vein of Arab architecture, at first glance may invoke an attempt to represent mass conformity within the ‘Islamic’ world in relationship to its most significant sacred congregational space – the Ka’ba - however, that does not happen to be the case. Langlands & Bell conceive of all architecture and architectural geometry as a reflection of the human will to impose order on chaos, and in turn that religious architecture reflects the human desire to formulate a ‘geometry of belief’ as a strategy to oppose the certainty of oblivion. Different religious traditions possess diverse philosophic, aesthetic, and tectonic practices devoted to achieving these objectives. Therefore, by organising through geometric or architectonic platforms, the emphasis of a religion’s respective congregation via a specific means, such as perspective and other systems of visual presentation and perception, as a mechanism, they engender a particular set of beliefs. Fascinated by the notion that the congregation in every mosque faces the qibla oriented towards Mecca, and that ideally every practicing Muslim will visit Mecca at least once in their lifetime, they regard this phenomenon as an extraordinary arrangement of time and space that connects every involved individual on a mass global scale. In essence, The Ka’ba is the geometric figure employed to generate this series of events.

Markedly, Langlands & Bell’s most profound work out of their three Arab architectural representations undoubtedly asserts itself in the ‘The House of Arabs’, 1990 (wood products, glass, paint, cellulose lacquer, 180 x 220 x 15 cm). The piece recreates the ground plans of three critical structures of paramount significance to the contemporary Arab world enshrouded in blatant political overtones: The League of Arab States, Tunis, placed at the centre; The Martyrs Monument, Baghdad, situated at the base of the composition; and The Circular City of al-Mansur, Baghdad, positioned on top. On an abstract, yet less significant level, their placement of the medieval Circular City of al-Mansur over the other two represented structures implied an elevated idealization of the Arab world once realized in the past that is now almost seemingly unattainable to achieve in the present. On a more critical basis delving deeper beyond a repressible romanticisation, this placement signifies the precise, enduring and articulate nature of the depicted symbol, the structure of and the circular sign for the city, which traces its origins to ancient Egypt. Fundamentally speaking, it indicates the ancient historical lineage of the city of Baghdad, and its connection to the present. This specific representation, as well as inserting the Martyrs Monument intended to coincide with the Gulf War, allotting specific contemporary relevance to the piece during the time in which it was created.

The inclusion of the League of Arab States in its previous location in Tunis alludes to the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty and the Camp David accords. The centrality of its position in the composition conveys Israel’s focal significance to the conflict present in the Arab world and the political discourse primarily associated with it. Provided that this sentiment does not contradict these parameters, illustrating the League of Arab States embodies a gesture of modernity, also referencing the wider political will to plan events that architecture encapsulates by elevating it to utopian ideals. Centering the League of Arab States in the composition of ‘The House of Arabs’ also brings these issues to the foreground.

Overall, the ordering of the depicted structures within ‘The House of Arabs’ meant to serve as a historical layering, referring to the past as a foundation of the present, arranging it in a scale or continuum, signifying the utopian ideal as the highest layer. In examining the overriding issues permanently embedded into the core of the Arab world resulting from the impact of the Napoleonic, colonial and post-colonial periods and the foundation of the state of Israel, the most contemporary and relevant issue current to the production of ‘The House of Arabs’ was placed at the base in order to reflect both its significance within the specific timeframe its associated with and the potential of its enduring impact in the future.

The seminal beauty of these aesthetically sleek and dichromatic sculptures manifests itself in the multilateral approach taken by Langlands & Bell in recreating and reinterpreting these architectural plans. They succeed in representing politically charged structures through a completely ‘apolitical’ perspective, eliminating the potential of expressing subjective social and political stances or impassioned nationalistic sentiments; on a superficial level, Langlands & Bell’s emotional detachment to the Arab world as Anglo-British artists accorded them this feat, also prevailing in refraining from ‘Orientalising’ their given subjects. Yet by and large, the artist’s capacity to isolate their subjects in order to be examined through an unbiased compendious standpoint, also in an attempt to assign them their utmost relevance to a universal present reality, remains to be their most innovative gesture exemplified through their three Arab architectural representations.