Photography by Sueraya Shaheen

Photography by Sueraya Shaheen

A Nationalism Among Nations: the Palestinian Pavilion in Venice

October 2009

“’Palestine c/o Venice’ underscores chronic impermanence, a condition Palestinians surmount with creative resistance as they reclaim their place as art practitioners free from the political essentialism that defines the media representation of their aesthetics…”

Salwa Mikdadi, curator of Palestinian Pavilion.

It’s interesting that we are able to achieve an official presence for Palestine in the 53rd Venice Biennale, ironically enough on Giudecca …I would have opted for a place in the Giardini..…sandwiched between the Israeli and the U.S. pavilions…

Jack Persakian, artistic director of Sharjah Art Museum, founder of Anadiel Gallery and the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in Jerusalem.

The uniqueness of the contemporary Palestinian predicament...requires a new conceptual framework, in addition to the colonialism/post colonialism and globalised post-modern paradigms.

Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, curator, and editor of “Palestine: Rien ne nous Manque ici” (Cercle d’Art, Paris)

These observations have been excerpted from the Palestinian Pavilion exhibition catalog.

The title for the Palestinian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Palestine c/o Venice, brims with a multi-layered meaning and various connotative references. ‘C/o’, that diminutive abbreviation, is gingerly placed as a bridge or a hinge to a door between Palestine and Venice, and encapsulates the debates that surround inclusion. The exhibit’s existence and process of becoming provides a mirror for the art world to hold up when examining the conflicting and intertwined issues of nationalism and identity. In this year’s Biennale, Palestine was given a ‘regulated’ passage into the realm of nations. Palestine c/o Venice is ironically and perhaps appropriately located on the island of Giudecca, a former Jewish ghetto, created and inhabited during the entire Renaissance, and whose residents were forcibly removed to pave the way for 17th and 18th century Italian villas.

Many of the artworks shown at most Venice Biennales showcase national pride. Daneil Birnbaum, this year’s director, continued to follow the evolving shifts in how the Biennial should ideally be viewed: “The pavilion system may appear obsolete, but it’s also a perfect platform to challenge notions of cultural and political identity.” (Frieze, June 09) Buried in what Birnbaum claimed is the admission that the Venice Biennale’s role has been and continues to be a nationalistic monster. Recent exhibitions’ oblique critiques of the strong nation-state are approached from the inside out, and from within the belly of the beast where true change sometimes occurs.

Since the mid-1990s’s, Vittorio Urbani’s organization Nuovo Icona, among other influences, has worked with the Biennale to delicately represent neglected countries/ethnic cultures, such as Ireland, Wales, Scotland, India, Finland, Lebanon, Uzbekistan, and Palestine. This directive resulted in a complex, yet soft-edged challenge to the notion of the nation state, one whose absorption of global transmigrations waltzes with vicissitudes of national identities evidenced by the number of cross-border pieces in this Biennale alone. Once having been an obstacle to these inclusions and discussions, Venice is now at the center. After all, Venice’s identity, its past as a major collector and trader of the world’s wealth, has been at odds with its more recent stodgy, inconsequential and hermetic role as the purveyor of taste and trends. Venice may be returning to its roots.

The Palestinian Pavilion existed prior to World War II through a European Jewish/Zionist initiative. For the 1949 Bienale, the name was changed to the Israeli Pavilion. At that time many, and until recently usually European nations were represented in the Bienale to the exclusion of others. Fast-forwarding to 2003, the director Francesco Bonami cleared a path for a Palestinian artist to enter through a side door that linked Palestine to Italy. The collaboration of the artist team, Palestinian Sandi Hilal and Italian Alessandro Petti was shown. Their installation of billboard-sized passports, ‘Stateless Nation’, grabbed the attention of the New York Times Magazine. In 2007, Palestine entered the Italian Pavilion with Emily Jacir’s installation ‘Material for a Film’, a work thickly laced with Italian history. Jacir grew up in Rome during her teen years and her piece examined the history of Wael Zuaiter. Zuaiter, living in Rome, was the first of many Palestinian artists and intellectuals to be assassinated by Israel during the 1970s and 1980s. Jacir won the Golden Lion Award for an artist under 40, and decidedly pushed the art world into embracing the cause of Palestine. Most importantly, the issue surrounding who can and cannot be admitted into the Biennale seems to have been rendered ambiguous at worst and a non-issue at best. These two steps led to this summer’s official inclusion of ‘Palestine’. In fact, for many, it was a seismic shift, almost in a sense like including Palestine in the Olympics.

Salwa Mikdadi comments on the interconnectedness between artists and adopted/adapted nations:

National representations and identity are no longer the parameters of international fairs and biennales. European borders are more porous and diaspora artists born in countries outside Europe are now representing their adopted country. For example, like the Olympics where origin becomes secondary, Moroccan born athletes represent France at international competition; in the 2007 Venice Biennale Iraqi born Adel Abidin participated in the Nordic Pavilion and Palestinian artist Emily Jacir in the Italian pavilion. The first participation of the Syrian Arab Republic featured nine participants: two Syrians and seven Europeans. This year the Nordic and Danish Pavilions will collaborate on one project…creating a “transnational neighbourhood” connecting the two pavilions in the Giardini, an area traditionally housing distinctive national pavilions. (Catalog entry)

In spite of the Palestinian Pavilion’s unresolved status and location, it was the most popular in Venice’s 2009 Biennale. Salwa Mikdadi admitted that her worries about the location and cumbersome access vanished when she saw the long lines outside the exhibit. The visitors, dignitaries and art patrons climbed into the vaporettos that sped them to the island of Giudecca. Apparently, the Palestinian Pavilion was a must see and the multitudes overcame crowds, canals and ironic meanings.

Under stringent standards of sponsorship and logistical maneuvering, this show delivered what it had promised to itself. Aside the fact that the artists’ work explored the various ways that resistance can manifest, the Palestinian community at large was challenged. Among those promises, the Pavilion’s expenses were covered from purely Palestinian sources. Palestinian funding organizations are usually tied to regulated sources in Europe and the Middle East, for they usually cannot affirm their culture within Palestine. Funds have to be teased out from the various international agencies to which Palestinian culture and aspirations have been tethered for over 60 years. Other obstacles included the lack of a tradition of supporting the arts among wealthy Palestinians. “Part of the point was to create urgency within the Palestinian community at large, to meet the challenge of making this exhibit a priority within its collective conscience.” Mikdadi asserts. Many Palestinian contributors entered the realm as art patrons for the first time.

“Palestine c/o Venice” refers to Venice’s big sister role, its shepherding of Palestinian artists. Another significant reference, to be taken literally, is to mail and postage. Palestinian artists have long given agency to banal objects. Postage stamps, postcards, pencil shavings, passports, luggage, road maps, hair, cages, “welcome” mats, almost anything becomes a device to construct narratives based on the alignments of past wrongs and the continued occupation of their lands. These objects are infused with meaning due to the fact that they are the domestic detritus that Palestinians stumble over. They are the endless symbols of their alienation, loss and dispersal. Just as piled-up shoes of Holocaust victims forever changed our understanding of what a pile of shoes may mean, the objects found in Palestinian art take on monumental significance, becoming unsettled memorials. Palestine is not resolved. The concept of ‘Palestine’ as a place hovers over its unfolding history. It has not settled into the dark and claustrophobic comfort of ‘memorial’ status. Taken as a whole, the six artists in the Palestinian Pavilion encompass this suspended and stark state of being.

The Palestinian Pavilion artists were selected from those who work in Palestine and those whose work pertains to Palestine. Unlike their intelligentsia forbearers, contemporary Palestinian artists have worked outside of the political choices that emerged after 1967. They form a consensus that zeroed in on the principles of anti-occupation and pro-boycott. They are aggressively critical of their aging and entrenched leadership from all political spectrums. Born out of necessity, Palestinian artists with one voice, but under a variety of means, are beginning to define what nations accomplish both from the inside and outside.

Three of the artists chose to break out of the normal parameters of the gallery. Emily Jacir spread out through the city, swimming in the canals. Hilal and Petti created a network of rapport among the whole of the biennale. And Khalil Rabah dispersed his installation by jumping to the other side of the Mediterranean with synchronized shows within Palestine.

Jacir’s ‘stazione’ attempts to break free of the exhibit location of Giudecca by broadcasting the Arabic language into the city at large, turning Venice into an official-looking bilingual state. ‘Stazione’ places Arabic instructional texts on stations and vaparettos to remind the viewers of Venice’s legacy to the Islamic world, and its equal importance of Arabic to the standard languages used in international settings.

Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti return to the biennale with ‘Ramallah Syndrome’ by using video and kinetic forms to link various voices to the spaces between nations. Conversations with various individuals and artists create a virtual and suspended community debating the socio-architectural city of Ramallah, and the hierarchy that was created after the demise of the Oslo Peace Accords.

Khalil Rabah’s piece ‘3rd Riwaq Biennale 2009, A Geography: 50 Villages’ is structured around questioning the spectacle of international exhibits. His vision is on a large scale in that it extends outside of the bounds of the gallery space and city of Venice to Palestine through various liaisons. Rabah offers varied spaces with which to experience contemporary Palestine. He does this by creating a dispersal of experiences rather than a centered one. The dispersal is aggressive and can be seen as a broad psychic assault on the restrictions of the past and present.

Two artists, Taysir Batniji and Shadi HabibAllah share a similar aesthetic in the hermetic nature of their practice. They both create the opposing states of distance and intimacy within the objects they use and manipulate. A kind of alchemical logic is in the works.

Pencil shavings reveal an obsessive process in Taysir Batniji’s Hannoun project. By contrast to the other artists, Batniji’s vision is highly idiosyncratic, personal and hermetic. Hannoun means poppy in Palestinian dialect. The pencil shavings refer to the monotonous and meditative act of field painting. The very act of creating the shavings reveals the artist’s existence in an isolated Gaza studio. Art production becomes a distanced space of oblivion and escape. Batniji describes Hannoun as, ‘...an impalpable landscape that one observes as in a dream from an un-crossable vantage point.’

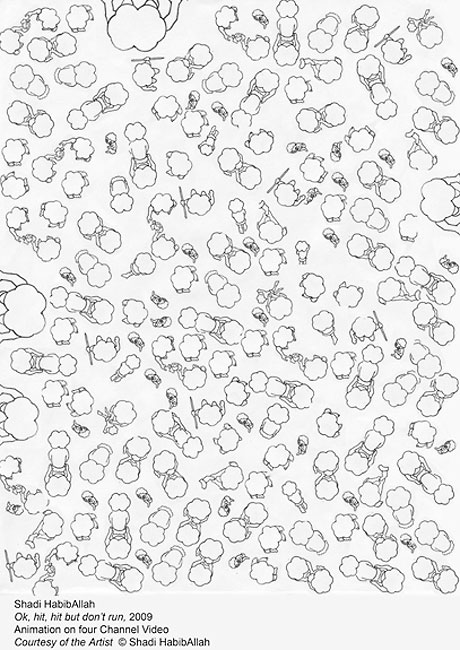

In Shadi HabibAllah’s ‘Ok, hit, hit but don’t run’ deploys video and kinetic sculpture to define the ‘thingness’ and physicality of objects from nature and contrasts them with the mechanized world. Through this, he disrupts realities based on absence and expectation. HabibAllah blurs the lines between the varying states of matter through an intimate play between words and process.

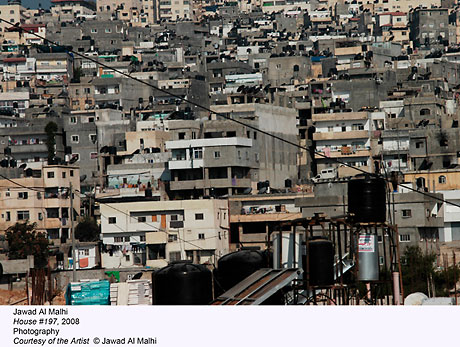

By contrast to his compatriots, Jawad Al Malhi brings into the work a more anthropological sensibility. However, it is very misleading to use the term anthropology for Al Malhi captures an element of intimacy that gauges his own complicity. Al Malhi explores the dynamic architectural structures of his refugee camp and how residents negotiate and compete for the shrinking space in which families can grow. This piece shows an accumulation of confined spaces stacked and disintegrated. It is the inverse of Jacir’s exploratory piece. The photos of the Shufhat Refugee Camp show observations from an adjacent settlement. They not only question the logic of birthrights attached to limitations, as they also examine the issue of cultural claustrophobia within the camp.

Taken as a whole, this exhibit explores interior and exterior modes of resistance. The artists collectively represent approaches toward coping with the unforgiving matter of identity and nationalism. Rabah’s concepts go beyond the confines of Venice by seeking a way out. He exploits the international spotlight on Venice to find a way back, a way to return to Palestine in the glaring light of day. Hilal and Petti’s ‘Ramallah Syndrome’ offers a potent assembly of collaborators that exhaust the debates around nationalism. It is by example, rather than argument that this issue is dissected.

The presence of the new participating nations in the Venice Biennale has altered the influence on nationalism and pedigree. Until recently, perhaps only ten years ago, the countries that participated seemed to embody the ‘white man’s burden’ of setting ‘standards’. Embedded into this exclusivity was the reason for the exclusion of others. The accumulation of subtle interventions since, by several curators and directors seems aggressively progressive in retrospect, given its unexpected push towards the acceptance of Palestine.

Can we measure Jacir’s ‘stazione’ text piece to that of Bruce Nauman’s recontextualized ‘7 Deadly Sins’? Does Al Malhi’s catalog of space go beyond anthropological journalism? Does Rabah’s challenge, now that he is showing within the high art world, upend the status quo of international art exhibits? HabibAllah and Taysir Batniji projects are deliberately meandering and searching. They offer a return to meditative groundings that are coupled to opposing states. In their narrow parameters there is interplay, dissolution and focus. The dispersed patterns that they find take us into the deeper recesses of the subconscious. However, another trajectory may have laid the groundwork for the prominence of Palestine. The Venice Biennale begins to recall Venice’s old role as an engaged trading magnet for the world surrounding it. One unexpected by-product is to rethink Western art. This year’s inclusion, for example, of Bruce Nauman’s piece ‘The Seven Deadly Sins’, takes on an eerily American cast, as it has not done before. This formerly free-floating piece with universal references now seems to be narrowly nationalistic, and about the specific sins that America committed as of late, given the economic crisis, rather than the broad meaning it once possessed 20 years ago.

Whereas non-Western artists were once relegated and confined to the awkward realm of identity politics or multiculturalsim, now Western artists’ national and cultural baggage needs examination. The art world of ‘Old Europe’ may have expanded to include ‘Old America’. Is the playing field being leveled and will it have continued traction? These questions have been given agency in part due to the evolving concept of “Palestine” under the wing of Venice.